INTRODUCTION

Few authors have grasped the realities of destruction and assaults on earthly tranquility as thoroughly as Leo Tolstoy. But for painting he assigned a special role: “Art should cause violence to be set aside. And it is only art that can accomplish this.

The great writer’s mandate is answered in a remarkable way by Masayuki Hara’s paintings. When there are clouds in Hara’s skies, they suggest a rain that will nourish the soil- never a storm that might destroy it. Those clouds blanket a unified landscape in which everything has its lush and rightful place. In any event, most often the skies are blue: a cool, almost silvery, unblemished blue that has the look of distillation - that beautiful and elusive sense of distance - that marks Hara’s forms and colors alike. Here is an artist of rare virtuosity and remarkable control. who has chosen with flawless precision his position, emotional and physical, in the landscape. The result of his supremely conscious care is that the woods and rocks and mountains have their own powerful voices, and that the viewer, whatever his usual artistic predilections may be, cannot help but feel transfixed.

It isn’t that Hara has turned his back on the realities of earthly existence, If he has totally eschewed violence and disorder in the ambiance of his work, he dwells nonetheless on every wrinkle on an old man’s face, on leaves that are dead and will soon disintegrate into the water upon which they float, on paint pealing off a shipwreck. What is significant is that with Hara’s vison the exigencies of life are somehow devoid of destruction. There is an order to things that we have come to expect as an inevitable part of some beautiful overall reality. Hara’s work has such an even tempo to it, his technique such paramount finesse, that we accept all in the same calm and benevolent voice.

Tolstoy wrote that “Art is a human activity having for its purpose the transmission to others of the highest and best feelings to which man has risen.” Hara is on the mark. He is sensitive to the world before him, passionate about the flow of water, the silhouette of grass, the wonder of light. He avoids any hint of the smugness or melodrama that often mar precisely realistic acuity. warmth and energy, pervade his work.

Born in Osaka in 1956, Hara has , at the age of thirty-two, already achieved great stature for a body of work that many would have been pleased to achieve in a long lifetime. Henry McBride once wrote that “Jhon Marin was born old and remained young;” in his skills and knowledge, his alertness and openness, the same can be said of Masayuki Hara.

Nicholas Fox Weber April/1988

[ taken from New York Hammer Gallery 2nd solo exhibition catalog]

Masayuki hara’s Landscape paintings of central and coastal japan achieve an uncommon- but immediately appreciable- balance between the specific details of identifiable sites and the commanding power of universal landscape forms. While from a distance, the viewer may find the compositions reminiscent of rural Maine or the mountain-fringed plains of the western United States, the nuances of texture and color,the carefully realized subtleties of architectural detail and plant life, quietly assert the geographic integrity of the paintings’ origins. The universality of their appeal is born of very self-conscious fidelity to the local truths of Japanese landscape.

Hara’s success in evoking the experience of the infinite from the undisguised commonplace or the narrowly circumscribed depends directly on the remarkable conjunction of his coloristic subtlety and his draughtsmanly power- the latter a skill which is only rarely devoted to landscape art today. The unfolding vastness of Hara’s spaces or the gritty immediacy of sand upon the bones of a fish remind us that it was in the painstakingly drawn and The unfolding vastness of Hara’s painstakingly drawn and delicately colored works of such other intensely observant artists as the brothers van Eyck or Bellini that the western landscape painting tradition originated. It is only in the past one hundred years that landscape paintings has come almost exclusively to mean a search for painterly effect and strong, light struck color. In the stead of landscape paintings that emphasize the materiality of their own surface, Hara gives us back the materiality of the landscape itself.

The exacting drawing and careful control-sometimes a deliberate celebration of the variability of atmospheric tone that characterize Hara’s larger landscapes give visible sensation to the tangibility of the sites he chooses: the textures of rock against foliage ; the palpable, rhythmic monumentality of the hills and plains surrounding lake Biwa; the limpid, damp embrace of morning mist. In the more intimate encounters with a single rock or a strand of grass, shells upon sand or a hayrick in the shadow, Hara’s meticulous attention to detail is set against stronger contrasts of light and shadow, without the mellowing effect of intervening atmosphere.

But whether seen from a vantage point of birds high in the hills, or of the solitary traveller on the deserted beach, Hara’s landscapes maintains a powerful conviction in the significance of detail within the whole. It is in his ability to balance the specific and the universal that Hara’s paintings transcend their own realism, to capture in single moments the enduring mysteries on the earth they record.

Alexandra R. Murphy

Curator of Paintings, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

April/ 1986

[taken from New York Hammer gallery 1st solo exhibition catalog]

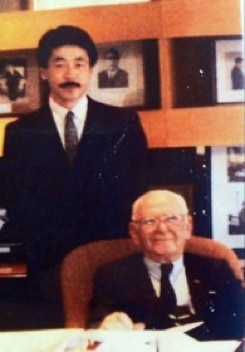

with Dr. Armand Hammer (1988)

1st. solo exhibition catalog in New York

2nd. solo exhibition catalog in New York

PUBLICATION :